Vargas Girls: From WWII Cheesecake To The Cars' 'Candy-O'

By | April 23, 2019

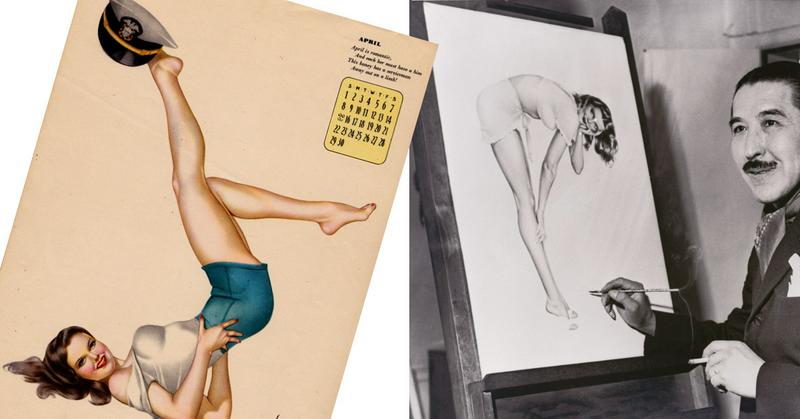

Early in the 20th century, an American visual style was invented by the Peruvian-born artist Alberto Vargas. The "Vargas Girls" he painted, as they were later known, appeared in magazines, advertisements, and calendars, and on posters and airplanes -- and for all he painted, infinitely more were created by others working in Vargas-inspired style. Vargas wasn't the only pin-up artist -- George Petty and Gil Elvgren deserve mention as well -- but the Vargas Girl brand he created has endured as the highest example of the genre. Vargas Girls became a staple of Esquire and later appeared in Playboy on a monthly basis.

Vargas' Early Professional Work

In May 1919, Alberto Vargas was painting in a store window, when a representative from the Ziegfeld Follies discovered him. The next day, Mr. Ziegfeld commissioned Vargas to paint watercolors of the 1919 stars of the Follies for the New Amsterdam Theater’s lobby; he would paint for the Follies for the next 12 years.

Vargas’s father was a photographer, and Vargas was exposed early on to the airbrush, a method that allowed for improvements to photographs. During a trip to Switzerland, he stopped in Paris, where he found his great inspiration: Raphael Kirchner, whose technique influenced Vargas’s development as an artist.

Vargas Goes Hollywood As A Movie Poster Artist

In 1927, after being hired by Paramount Pictures’ art department, he created the original artwork for the film Glorifying the American Girl, which was produced by Ziegfeld. He also created covers for Tatler and Dance magazines and designed countertop displays for Old Gold cigarettes. When the Great Depression hit in 1933, Vargas had trouble finding work and moved with his wife and muse Anna Mae (nee Clift) to California. There he continued to paint movie posters; his best known, for its pose and near-nudity, is The Sin Of Nora Moran, which depicted Zita Johann on the verge of a wardrobe malfunction.

In 1939, Vargas and some other unionized movie-studio artists walked off the job in protest -- and Vargas was blacklisted. Suddenly, he couldn't get work in Hollywood and was forced to move back to New York.

The Invention Of The 'Varga Girl'

Vargas' first published Varga Girl appeared in the December 1940 issue of Esquire. Since its first issue in 1933, Esquire always contained a pinup girl, painted by George Petty and known as the "Petty Girl." The pin-ups were perhaps the most popular regular feature in the magazine and thought to ensure circulation. In 1940, Petty pushed for more money, and refused to contribute unless he got it -- Esquire decided to hire Vargas, by then an established calendar artist, rather than cave to Petty's demand.

As explained in an account of the artist's life in Cigar Aficionado, Esquire more or less exploited Vargas. Whereas Petty had been getting upwards of $1,800 per painting, Esquire co-founder David Smart had Vargas sign a contract that paid him $75 a pop. Smart also stipulated the works be signed "Varga" (without the "s"), a name that would be owned by Esquire. In essence, Vargas signed away all rights to his own art, for peanuts. Vargas signed a new contract in 1944 that offered slightly better compensation but demanded an insane amount of work. He was among the most famous artists in the country, his images were carrying Esquire, the magazine was making an estimated $1 million off of him annually, but Vargas himself wasn't seeing the prosperity.

At one point, the U.S. Postal Service sued Esquire for shipping obscene material since the magazine contained images like the Vargas’ girls; Esquire won the case, which went all the way to the Supreme Court.

Varga Girls Go To War

Vargas, who was a passionate artist rather than a businessman, spent the early '40s -- World War II -- bursting with patriotism rather than fuming over his awful Esquire contract. U.S. soldiers loved their Varga Girls, and the artist churned them out almost as part of the war effort. Esquire was sending crates of its magazine overseas, to be distributed for free. Varga Girls (and pinups by other artists) became favorites subjects for bomber jackets and the "nose art" that adorned bombers.

With her long legs, a narrow waist, voluptuous figure and ever-present adoring smile, the Vargas Girl was a sexualized “girl next door” who boosted morale for the soldiers fighting abroad. These images were literally going to war; this style of cheesecake, of which Vargas was the master, was as American as apple pie.

The Vargas Technique

The style Vargas perfected at Esquire involved producing three preliminary studies on tissue paper, progressively adding details to the final study on heavy parchment paper. That final study was nearly identical to the eventual painting. Vargas completed the initial studies with the model in the nude, adding clothing to the final portrait. This last part -- adding the clothes -- would be less necessary for Vargas' next employer.

Hugh Hefner To The Rescue

Eventually, Vargas got fed up with his treatment by Esquire and sued. He parted ways with Esquire in 1947, continuing to work on his annual calendar and to take on commercial assignments. The legal battle was long and costly for Alberto and Anna Mae. When in 1950, Anna Mae required a mastectomy, the couple was broke and their doctor paid for the operation.

Vargas came to the attention of Hugh Hefner in 1957, after Playboy magazine published a feature on Vargas’s nudes, and Hefner sent him a personal invitation to work for the magazine. His work would appear monthly in Playboy; he would paint 152 Vargas (with an "s") Girls for the magazine over the course of 16 years. The images in Playboy moved from the playful images that Vargas created, taking a more sexual tone.

The Vargas Work Everybody Knows Best

Vargas’s paintings are closely connected to the time period they were produced in. Each of his girls reflects the standard of beauty as well as the mores of the time period.

He stopped painting, almost completely, when his wife died in November 1974. He completed album covers for Bernadette Peters and one for The Cars’ album Candy-O before he died in 1982 -- for members of the public who don't recall his work from WWII or '60s Playboy, the Candy-O cover is undoubtedly his best-known piece.

A Lasting Influence

Vargas girls, or illustrations borrowing heavily from Vargas' style, appear on a variety of playing cards, bubble gum containers, greeting cards, and of course, calendars. The image of a Vargas girl was even used by Sheetz, a convenience store chain.