The 1979 Three Mile Island Meltdown Made 'China Syndrome' Seem Prophetic

By | March 20, 2019

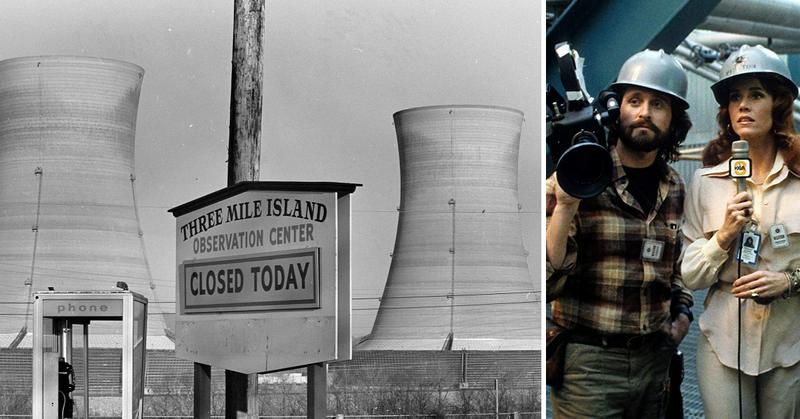

There's one place-name that will always make Americans balk at the idea of "safe" nuclear power: Three Mile Island. The nuclear reactor complex in Pennsylvania was the site of a partial nuclear meltdown in 1979, and what's worse, the chain of events had a lot in common with The China Syndrome, a disaster movie in theaters at the time. It was a PR nightmare for the Three Mile Island facility -- and a PR bonanza for the film. For an American public that had been struggling with an energy and gas crisis, the Three Mile Island incident was more than a little disheartening.

In the decades following World War II, the public was told that the nuclear age promised more than just apocalyptic warfare -- atomic power was billed as clean, inexpensive energy. Eyes were opened in March of 1979 when the nuclear power plant at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania experienced a partial meltdown, leading to the biggest nuclear disaster in the history of the U.S. nuclear age. At the time, nearby residents of the nuclear power plant had no idea how close they came to being showered with potentially-lethal radioactive gases. Let’s look at an overview of the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster that almost melted a hole in the earth all the way to China.

Three Mile Island And 'The China Syndrome'

In early March 1979, the disaster movie, The China Syndrome, starring Jack Lemmon, Michael Douglas, and Jane Fonda, was released. Following the trend of other disaster movies of the 1970s, The China Syndrome focused on a deadly meltdown at a nuclear power plant. The name of the movie was taken from a phrase stating that a nuclear meltdown could be so bad that it would melt a hole deep into the Earth all the way to China. When the movie was released, the United States's nuclear power industry panned it, claiming that the film was pure fiction and that it smeared the exemplary reputation of nuclear energy. Twelve days later, the Three Mile Island accident occurred. The China Syndrome helped fan public fears after the accident. But the accident also helped the movie sell more tickets.

A Routine Task Sparked Near-Deadly Chain of Events

What started the sequence of events that led to the partial meltdown of Three Mile Island’s reactor was a simple, routine attempt by the operators to unclog a water filter blockage in Unit 2 while keeping it running at 97-percent capacity. This was because Unit 1 was down for maintenance. Things started the downward slide when the water pumps that were supplying Unit 2’s steam-powered generators shut down. This caused heat and pressure to build up inside the cooling system of Unit 2. There were safety measures in place to solve this problem. The system initiated an automatic shut-down of the nuclear reactor, just as it was designed to do. But there was one little problem.

From Bad To Worse

Heat and pressure were still building up in the cooling system for Unit 2, even though the reactor was shut down. Secondary water pumps kicked on automatically, but some of the valves had been closed during the original maintenance process, meaning no more cooling water could enter Unit 2. It was later revealed that the closed valves were a violation of federal safety regulation, but there was a more pressing problem at hand. The reactor in Unit 2 was way too hot.

A Sticky Valve

Plenty of safety measures had been built into the nuclear reactors at Three Mile Island. One such measure was a release valve that would help vent excess pressure. The heat and pressure build-up in the reactor triggered the system to open this valve, which it did. The operators could see an alert on their control panel indicating that this valve was open. The valve was designed to automatically close once the pressure was regulated. In fact, the operators’ control panel alert indicated that the valve was shut again. But it wasn’t. Somehow, the valve failed to close and was stuck open. Unit 2 was losing its coolant. Steam from the cooling water was quickly escaping through this open vent and the operators were unaware of it.

An Out-Of-Control Disaster

Unbeknownst to the plant’s operators, the release valve stayed open for hours, allowing precious water to escape—water that was needed to cool the reactor. Without water to cool it, the reactor’s rod continued to heat up until they became so super-heated that it experienced a partial meltdown. The operators, still unaware of the open valve, thought that the problem was too much water in the cooling system…the exact opposite of the actual problem. The operators turned on the emergency cooling pumps, but this just set up the next catastrophe.

Raising Radiation Levels

Several hours into the disaster, the relief tank split open, spilling radioactive coolant into a general containment building. It was only at this time—hours after the start of the problem—that alarms began to sound alerting the Three Mile Island employees of serious radiation levels. The general containment building was quickly contaminated with dangerous levels of radiation and the radiation levels in the coolant water were at least 300-times the normal levels.

Federal And State Authorities Are Alerted

On the morning of March 28, officials at Three Mile Island finally alerted state and federal agencies about the problems at the nuclear power plant. These state and federal agencies were concerned about the levels of radiation that could threaten the nearby residents. What no one realized at the time was that the core of the nuclear reactor had already melted even as the operators were frantically trying to manage the cooling of the super-heated reactor. Later that morning, the White House was notified about the nuclear accident.

Evacuations

As the radiation levels were being monitored in and around Three Mile Island, the governor of Pennsylvania, Richard Thornburgh, was being continuously updated. The public was on edge and rumors and false news was rampant. The China Syndrome had shown them the horrors that could come with a nuclear reactor meltdown. All non-essential workers at Three Mile Island were evacuated from the plant. Many nearby residents fled the area. Others awaited official updates. Two days later, Governor Thornburgh suggested that all pregnant women and families with young children living within a five-mile radius of Three Mile Island evacuate. This touched off more of a panic and a rush to leave the area. Thousands of people jammed the highways.

A Lethal Bubble

Even as residents were fleeing the area, the Unit 2 reactor at Three Mile Island was experiencing another, potentially catastrophic threat. A hydrogen bubble in the containment area of the reactor’s core was growing larger and larger. There was fear that this bubble could burst, damaging the containment area so much that the deadly radiation could no longer be contained. If this happened, a large area surrounding the nuclear plant would be destroyed and contaminated. Ironically, one prophetic line from The China Syndrome stated that the nuclear disaster in that movie could create a wasteland “the size of Pennsylvania.” It seemed that this scenario might come to pass.

The Threat Of Nuclear Destruction Subsided

Fortunately, the apocalyptic scenario didn’t happen. By the next day, the bubble was shrinking in size and pressure was released. The core was cooling down and becoming more stable. Remarkably, no one was killed in the nuclear accident, however, there are ongoing scientific studies to track thyroid cancer cases in people who were living near the Three Mile Island plant at the time of the disaster.

A Slow, Slow Cleanup Process

After many years, the radioactive material was finally safe to start the cleanup process at Three Mile Island. The fuel was removed beginning in 1985, nearly six years after the meltdown. Off-site shipment of radioactive debris began the next year, with the core material being sent to the Department of Energy’s Idaho National Laboratory. The removal process wrapped up in 1990, then the process of decontaminating the accident-generated water—nearly 2.23 million gallons of water—got underway. It took three years to finish this task, which concluded in 1993.