Mikhail Baryshnikov: How A Ballet Dancer Became A Cold War Celeb

By | January 26, 2021

When he defected from the Soviet Union in 1974, Mikhail Baryshnikov was arguably the best ballet dancer in the world. His status as a defector certainly made him the most famous dancer in the world. During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union fought many proxy battles that didn't involve weapons -- often at the Olympics, but also in the arena of culture. The U.S. was all too happy to welcome writers and artists who fled (or were expelled from) the oppressive Soviet state.

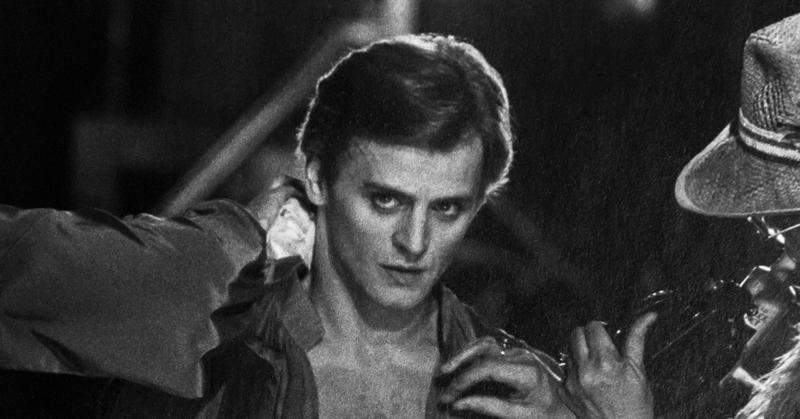

Americans aren't generally fans of ballet, but everyone knew the name Baryshnikov for what he represented -- and it didn't hurt that he was (and still is) exceptionally good looking.

In Russia, Ballet Is A Source Of National Pride

Ballet in Russia has a long history, beginning in 1738, when Jean-Baptiste Lande opened Russia’s first professional ballet school in St. Petersburg, initially teaching six boys and six girls who were the children of palace servants. Thirty-five years later, Filippo Beccari, began teaching orphans in Moscow. The two schools joined and Russian leaders worked to make ballet an art form. They coaxed foreign dancers to come to the country and by the 1930s, they began focusing on a training method named after Agrippina Vaganova, a method which focused on analytic approach to teaching ballet. Russian dancers are taught to use their arms and backs, which provides them with the power they need to turn and jump; young dancers are also taught to make even the exercises expressive.

For the Russians, ballet is a point of pride as dancers impress audiences with their technical ability, although some complain that the Russian tradition is too focused on technical perfection and lacks creativity. In the Soviet era, Russian ballet excellence carried a political message as a kind of advertisement -- figure skaters, weightlifters, classical musicians, chess grandmasters and ballet dancers were all testament to the miracles of the communist state.

American ballet, on the other hand, really started with George Balanchine, who had trained in Russia and emigrated to America, and although his style was derived from Russian ballet, he made it distinctly American, changing some of the movements.

The Cold War Put The Squeeze On Artists

During WWII, the Soviet Union began to annex Eastern European countries, forming the Eastern Bloc and tightening their hold on Eastern Europe. After WWII, when the Cold War began, the Eastern Bloc governments began to severely restrict emigration in order to stop their professionals from fleeing to other countries. Eventually, the few who were able to get out had to defect from the country. Vaslav Nijinsky was able to travel with more freedom because of the time he was active as a dancer, which was before the height of the Cold War. Rudolf Nuryev defected in 1961, but he was allowed to return for a performance in 1989. Shortly before Baryshnikov’s defection, Natalia Makarova defected in 1970.

Baryshnikov Began Dancing At Age 12

Mikhail Baryshnikov was born on January 27, 1948 in Riga, Latvian SSR (today the country of Latvia). His mother, who committed suicide in 1960 when he was 12, introduced him to theater opera, and ballet. The year his mother died, he began studying ballet. Four years later, he entered the Vaganova School in what was then Leningrad. He won the top prize in the junior division of the Varna International Ballet Competition and then joined the Mariinksky Balley, which was called the Kirov Ballet. He came to the attention of several prominent choreographers, who choreographed ballets for him. They noted his stage presence and the purity of his technique, and he was attracting international attention as well, as New York Times critic Clive Barnes said he was “the most perfect dancer I have ever seen.”

Baryshnikov Decided To Defect For Artistic Reasons

Because Baryshnikov was shorter than most dancers, he did not tower over a ballerina en pointe, and therefore only received secondary parts, which was frustrating because he was so talented. He was also frustrated by Russian choreographers who shunned Western choreographers and stuck closely to traditions. On June 29, 1974, while touring in Canada, he defected, requesting political asylum in Toronto. He had been planning his defection for four years, which he has said was more for artistic than political reasons as he wanted freedom to dance with the ballet companies in the West. As he said in an interview with The Globe and Mail in 1974 after his defection,

What I have done is called a crime in Russia … But my life is my art and I realized it would be a greater crime to destroy that.

He executed the plan while on tour in Canada; the Kirov Ballet had loaned him to the Bolshoi Ballet so that he could participate in the tour.

A Secret Call, A Crowd Of Fans, A Getaway Car, A Safe House

The actual defection was a daring episode. While on tour, the KGB watched Baryshnikov's every move. In fact, they had told him that while he was on tour in England in 1972, they had noted his every move and every word. Clive Barnes contacted a Toronto arts reporter John Fraser to ask him to pass a phone number along to Baryshnikov and give him the message to contact friends in New York. Baryshnikov managed to elude the KGB minders to make the call. On the night of the final performance in Toronto, the minders were trying to usher the dancers into the bus; while his height did not help his dancing career, it did help his defection as it allowed him to blend into the crowd that surrounded him to ask for autographs. He took the opportunity to run down the street where a getaway car was waiting. Jim Peterson, a lawyer, drove him to a farm outside Toronto. There, he hid until his political asylum papers were ready. Once he came out of seclusion, his first televised performance after his defection was in La Syphilde with the National Ballet of Canada.

Coming To America

Baryshnikov also began dancing with the American Ballet Theater as their principal dancer from 1974-1978. He danced with at least 13 different choreographers in the first two years after his defection, including Alvin Ailey, who fascinated him, because Ailey incorporated classical and modern technique in his choreography. In 1978, he spent 18 months as the principal for the New York City Ballet, dancing under Balanchine, who, incidentally, had refused to work with other Russian defectors. His last performance with the New York City Ballet came in La Sonnambula, in which he had the role of The Poet; after the performance, he took time off to let his tendinitis and other injuries heal.

In 1980, he became the artistic director of the American Ballet Theater, and he remained in that position until 1989. He also continued to dance with other companies, appearing in roles that were designed for him. Then, from 1990-2002, he was the artistic director of The White Oak Project, which he founded with Mark Morris; the White Oak Project, a touring company set out to create original work for older dancers. In 2000, he was awarded the national medal of arts, and has received honorary degrees from three universities, among other recognitions and awards. He opened the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York in 2005.

Baryshnikov Lived The Good Life In New York City

Once settled in New York City, Baryshnikov was the most famous dancer in town, and moved among the celebrities and cultural elites. He was regularly seen at fashion shows, museum events, and, of course, Studio 54, where he hobnobbed with Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger. Baryshnikov had a long relationship with Jessica Lange -- when he first met her, he hadn't yet learned English, so they conversed in French -- that produced a daughter. He dated other high-profile women, including Tuesday Weld and Liza Minelli. Baryshnikov had stated he didn't believe in marriage, but eventually did tie the knot with dancer Lisa Rinehart, with whom he has three children.

Baryshnikov Did More Than Ballet

By 1977, he made his first film, Turning Point, and he was nominated for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe. In 1985, he appeared in White Nights with Gregory Peck and That’s Dancing! which was choreographed by Twyla Tharp. He also appeared on stage in avant-garde theater starting in 1989.

He Still Has A Connection To Latvia

Baryshnikov never returned to the Soviet Union; he was informally invited to return in 1989, but it fell through. On July 3, 1986, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Then on April 27, 2017, the Latvian government granted him citizenship for extraordinary merit, after he applied and wrote them a letter, in which he stated that "It was there that my exposure to the arts led me to discover my future destiny as a performer. Riga still serves as a place where I find artistic inspiration."