How MAD Magazine Covered The '60s: What, Me Hippie?

By | April 16, 2019

In the ‘60s, MAD magazine covers grappled with issues of the day as much as any newspaper's editorial page. The images frequently played to both sides of an issue, whether it was drugs, mysticism, or politics. MAD was hip, in its way, but its mascot Alfred E. Neuman was, as ever, an idiot. The easy joke, especially when you're trying to sell magazines to younger people, would be to make fun of the out-of-touch older Americans. MAD, though, took the contrarian position, poking fun at the goofiness and even hypocrisy of the flower children. Neuman was often chasing trends, jumping on whatever ridiculous bandwagon was getting press. The writers and artists (namely Jack Davis and Norman Mingo) behind this unsuitable periodical delivered fierce indictments of anything they saw as important, hypocritical, or just plain stupid - anything and everything was in the crosshairs of MAD.

In the drugged out, love obsessed '60s, MAD lambasted the hippies and took politicians to task. The magazine wasn’t subtle, and it played devil's advocate whether its readers wanted it to or not -- but it was funny as hell.

January 1968: Take A Trip

In January 1968, MAD magazine offered readers to “take a trip.” This cover is obviously playing off the idea of young members of the counter culture getting high and taking a trip, but because it’s MAD they boiled it down to its most simplistic and moronic (in a good way) in order to offer up that most classic of comedic visuals - the banana peel.

This cover presents an obvious joke, but MAD never pretended to be above making a joke that anyone could have thought of. After all, someone else may have thought of it, but MAD printed it.

A Facebook follower reminds us of another level to this gag -- that some hippies (broke ones) were known to smoke banana peels in the mistaken belief that they contained a hallucinogen. What may have started as a joke evolved into a bona fide hoax when hippies actually offered instructions for extracting the fictional chemical "bananadine."

A Don Martin cartoon entitled "A San Francisco Trip" within the pages of this issue ties it all together. A shirtless longhair stands in his kitchen eating a banana. He scrapes the inner lining of the empty peel (that's where the bananadine lives) into a frying pan, then drops the remainder of the peel on the floor. He fries the scrapings, puts them in his pipe, and attempts to smoke it, but to no avail. He angrily throws his pipe, slips on the banana peel, bangs his head on the stove and falls into a dazed, hallucinatory state.

Confusing a slip on a banana peel with an acid trip demonstrates a classic MAD tactic: Picking up on a term or phenomenon from the cutting-edge culture and intentionally misunderstanding it. The "trips" people were taking in 1968 were voyages of the mind -- MAD misses the point completely, on purpose.

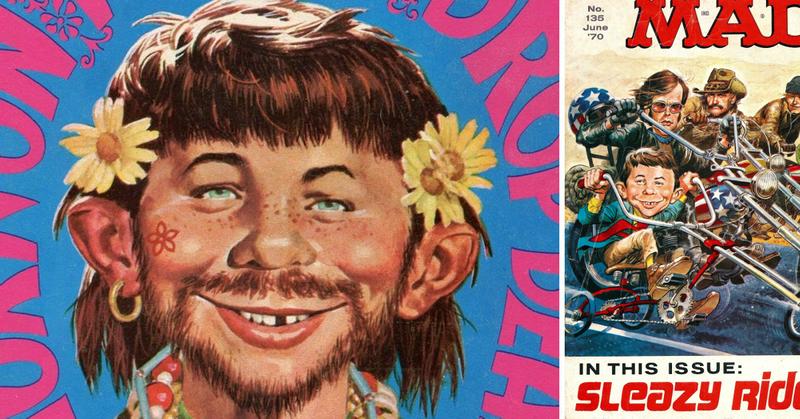

April 1968: Turn On, Tune In, Drop Dead

Proof of MAD’s ability to be incredibly nasty and subversive, the cover for their April 1968 cover takes the hippies and their free love attitudes to task. Not only does the magazine eviscerate the love children of the ‘60s with its design straight from a blacklight poster, but by putting MAD’s mascot, Alfred E. Neuman, in classic hippie garb it exposes just how silly these free love fans are.

Timothy Leary's famous, though slightly puzzling, slogan of "Turn on, tune in, drop out," is changed to "Turn on, tune in, drop dead."

There are a lot of things to like about his cover, although the cherry on top of the whole shebang has to be the bell that’s tied around Neuman’s neck. There’s just something so ridiculous about that image -- while he's on trend with the love beads, his constant ringing will announce his presence like a cow wherever he goes.

September 1968: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

The celebrity fascination with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was reaching its ridiculous boiling point, with the Beatles, the Stones, Donovan and others practicing what he preached and journeying to his headquarters in India. But who was this guy, and who decided he was the be-all and end-all of the satisfying, spiritual life?

MAD put its doubt about the Maharishi front and center, depicting the questing Beatles and Mia Farrow raising up the next wise man, or idiot savant: Alfred E. Neuman. Because if the Maharishi can waltz in and convince everyone to meditate, who's to say someone else might turn the leader into a follower?

The Hindu-looking text around the margins is the lyrics to "Swanee," rewritten as "Swami."

September 1969: The Generation Gap

In the '60s, America was splitting along generational lines, with parents increasingly puzzled or angered by their kids' beliefs and choices. And on the flip side, the kids were convinced their parents had it all wrong -- "Don't trust anyone over 30" (coined back in 1964) was their mantra. While many young people protested the Vietnam War and marched for equality, their parents were more likely to support and trust the government and military, and had trouble dealing with the racial strife and changes. The younger generation was trying drugs, growing their hair long, dressing in bizarre clothing, and listening to music that was far removed from jazz standards and even Perry Como.

This cover depicts a father and son separated by their choice of clothing, grooming, and slogans. They have nothing in common -- and yet, they're nearly identical. The two halves of Alfred E. Neuman's grinning face could be suggesting that the generations have more in common (idiocy) than we think, although that might be a stretch. One of the great things about MAD was that it gleefully skewered trends, assumptions and heroes without forcing any hokey messages on its readers.

June 1970: Sleazy Riders

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, MAD dedicated more and more energy to film and television parodies, but in 1970 it was still a novelty to make fun of a blockbuster. Ripping into the groundbreaking Easy Rider (released in 1969) was certainly up this magazine’s alley. Not only did it offer the writers a chance to skewer popular culture, but as beloved as the film is, there’s a lot to laugh about in this elevated biker flick.

Initially the cover art looks to be like any other MAD cover. It offers slightly distended versions of stars we all know, but the image of Alfred E. Newman riding a Schwinn with a set of ape hangers in a three piece suit is absolutely timeless.

December 1970: The Magazine Of The Loud Minority

This magazine cover from December of 1970 that plays on the concept of the "silent majority," coined by President Nixon in 1969, is among the best that MAD ever released. Not only does it have a goofy pun in “Beat State,” but the amount of detail on this cover allows the viewer to take their time looking at the art and finding nuances within the drawing.

The central irony is that the hippies, for all their sloganeering about "peace," are clearly violent and even crazed. They've knocked a policeman unconscious; there are the typical primitive rioters' weapons of bricks, bottles and a (broken) baseball bat at their feet; and they're angrily taunting the viewer. For the proponents of peace, they sure do seem like they want to fight.

Once again, MAD paints itself (or its mascot) as out of step with the times. While the headline-grabbing hippies rage around him, Alfred E. Neuman displays his innate squareness by supporting a football team. He represents Nixon's silent majority -- his traditional interests won't make the nightly news the way protesters' exploits do, and he's passionate about football, not war. We can't know what he's thinking, but it's possible that he has even wandered into this massive protest under the impression that they are fellow football fans -- he's that clueless.