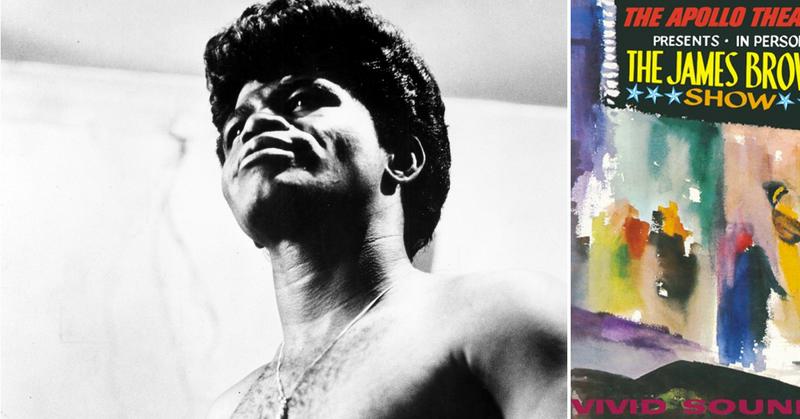

With 'Live At The Apollo,' James Brown Invented The Live Album

By | May 26, 2019

Before James Brown's Live At The Apollo (1963), record labels weren't sold on the idea of live albums. And after? Well, consider everything from Johnny Cash's At Folsom Prison to The Who's Live At Leeds to Peter Frampton's Frampton Comes Alive! a descendant Brown's brief crowd-pleaser. It had everything going against it -- the format, the song selection, the crowd noise -- and just one thing in its favor: James Brown's relentless belief in himself. Playing show after show to hysterical, screaming audiences, Brown knew there was value there for listeners that label honchos couldn't understand and producers in a sterile studio couldn't duplicate.

For decades afterward, any act that prided itself on its live shows dreamed of proving it on wax with their own equivalent of Live At The Apollo. And remarkably, nobody quite did it. Fifty-five years after its release, James Brown's Live At The Apollo remains the critics' consensus pick for best live album of all time.

Out of all the musical giants who graced the stage of the Apollo, none of them moved the audience the way that James Brown did. After a five day run at the theater in 1962, Brown and his group, the Famous Flames recorded a live album that that only lasts a hair over 30 minutes, but that’s all it took to create a career-defining masterpiece.

As listenable and poppy as Brown’s first “Live at the Apollo” album is, it’s inherently weird. Most of the songs are around three minutes long, save for the ten minute “Lost Someone” and the six-minute medley of hits. With “Live at the Apollo” Brown was showing the world that it was star time.

Brown’s Label Wouldn’t Pay For The Album, So He Foot The Bill

Brown and his band had been on King Records since 1960, and while the singer’s “Please, Please, Please” (released on the Federal label) sold a million copies, the head of King didn’t think it made sense to release a live LP for an artist who couldn’t move full-length albums and who was mostly a live draw. Rather than accept the decision of his label boss, Brown paid for the recording of the album and rental of the Apollo on October 24th, 1962.

By the time the group recorded at the theater they’d been playing there for five days straight and it shows. The group is hot and the audience gives just as much to Brown and his cohorts as the band gives to them.

“Lost Someone” Is The Album’s Lynch Pin

If you’re just coming to Live At The Apollo from the context of a modern live album then the record initially feels so strange. Current live albums tend to be bloated, maybe even double-disc affairs, but Brown’s first live LP is a spartan album with only eight tracks. However, the ten minute long “Lost Someone” is the glue that holds the entire album together.

Punctuated by the screams of the female members of the audience, the track is a downtempo groove that puts all of Brown’s charisma on display. By the end of the song, Brown is in full conversation with the audience. When he screams, they scream. It’s as if the audience in the Apollo that night were waiting for Brown to give them some kind of release.

Brown’s Label Didn’t Want To Release The Album

After delivering a mix of the album to Brown’s label, King Records, the label head, Syd Nathan, balked at releasing it. He felt that a live album with no new songs would be a death sentence for the LP. After pressure from Brown, the album was released a full seven months after it was recorded.

Released in May 1963, Live at the Apollo was a major hit. Any reservations about Brown’s star power were erased after the album spent 66 weeks on the Billboard album chart, peaking at number two. The album eventually went platinum, a first for Brown, but definitely not his last.

Brown’s Label Initially Released The Album With Different Album Noise

For some reason, King Records was dead set on ruining Live at the Apollo. Initially, they didn’t want Brown to record the album, and when he paid for the whole thing and delivered the album to their doorstep they didn’t want to release it. When they were finally strong-armed into putting out the record they decided to do it with canned audience applause. It’s as if they didn’t even understand the appeal of the record.

Brown obviously knew that the crowd was such an important part of his sound, after all, he placed microphones above the audience to better capture their screams. Thankfully, the only version of the album that exists is the one with the sounds from the Apollo audience.

The Album Inspired A Proto-Punk Classic

James Brown was the hardest working man in showbiz, and as such he’s inspired a lot of musicians from different genres to up their games. MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer said that one of the main inspirations behind their blistering track “Kick out the Jams” was Brown’s Live at the Apollo, he explained:

Our whole thing was based on James Brown. We listened to Live at the Apollo endlessly on acid. We would listen to that in the van in the early days of 8-tracks on the way to the gigs to get us up for the gig. If you played in a band in Detroit in the days before The MC5, everybody did 'Please, Please, Please' and 'I Go Crazy.' These were standards. We modeled The MC5's performance on those records. Everything we did was on a gut level about sweat and energy. It was anti-refinement. That's what we were consciously going for.

The Master Tapes Were Lost (For A While)

For the longest time Live at the Apollo was unavailable on CD and the transfers for the cassette and eight-track were less than desirable. Many master recordings from the early ‘60s were locked up and stored in a vault only to be forgotten after a few years. Artists and labels simply weren’t concerned with reissues and remasters. In the booklet of the reissued Deluxe Edition of the album Harry Weinger explains how the lost masters of the album were found:

Finding the primary master, not the readily available copy, became a mission. It was tough to find, since the original LP didn't index individual tracks, meaning its song titles would not be properly listed in a database. The tape vault was 100,000 reels strong, and growing. As JB would say Good gawd. I shared this tale of woe with Phil Schaap, the noted jazz historian. One day, Philip was searching the vault for a Max Roach tape, his hand landed on what he thought was Max's master. Pulling the tape off the shelf, he realized he had instead an anonymous-looking audiotape box that said: 'Second Show James Brown'. It was initialed, in grease pencil, 'GR-CLS-King Records' Gene Redd and Chuck L. Speitz. Phil handed it to me, saying with urgent economy, 'I think you need to hear this.