What's a 'Stepford Wife'? The Anti-Feminist Stereotype Created By A Movie

By | September 15, 2022

Even if you've never seen The Stepford Wives, the dark 1975 film sci-fi/horror film where wealthy suburban men turn their partners into subservient robots, you know what a "Stepford Wife" is. A Stepford Wife isn't just perfect, she's too perfect. There's an eerie, robotic quality to the way that she goes about her day and dotes on her husband. Subservient and docile, the Stepford Wife is a thing that should not be.

The Stepford Wives get their name from Stepford, Connecticut, the fictional town (based on Wilton) in which the eerie and attractive wives live. These characters were played by actresses known for their model-caliber beauty, including Katharine Ross, Paula Prentiss, Nannette Newman and Tina Louise.

Too good to be true

There are at least three iterations of The Stepford Wives and multiple, lesser, spin-offs, and while each version of the story packs its own specific punch it's the phrase that seems to stick with the population, not the story, not the harrowing images on the big screen. Decades after the film's initial release and slow journey to cult status, the term "Stepford Wife" has nestled into the vernacular at large to describe anything that's too perfect, or too good to be true.

What is a Stepford wife?

To put it simply, a Stepford Wife is a submissive woman who puts her husband's wants and needs ahead of hers while maintaining an immaculate personal appearance. Eternally youthful and docile, the term is full of venom. No one should be excited that they're fulfilling the Stepford ideal of perfection and servitude unless it's something to which all parties have consented.

In Ira Levin's 1972 novel and Bryan Forbes' 1975 film, Stepford Wives were robotic versions of a woman, refitted to be a better version of someone's partner. Their bodies are sculpted and their minds are molded to be exactly what their husbands want. The Stepford Wife doesn't want anything more than to serve because that's how she's programmed. Nanette Newman, who starred as Carol Van Sant in the 1975 adaptation described the robotic women to Entertainment Weekly in 2017:

A Stepford wife epitomizes somebody who is perfectly made up, looks perfect, and presents a very perfect facade.

The trap of normalcy

The 1972 novel and 1975 adaptation of The Stepford Wives lay out all we need to know about these nefarious automatons who've invaded normal life. Author Ira Levin is no stranger to the horrors of suburban, middle class life. The Stepford Wives, like his 1967 novel Rosemary's Baby, warns of the menace hiding behind the fake smiles and well constructed architecture of the good life.

Suburban prison

For Levin, the promise of the perfect home, the perfect family, the perfect wife is a trap. Perfect doesn't exist without strings attached. In Rosemary's Baby those strings are an eternity of servitude to Satan. In The Stepford Wives it's killing your wife and replacing her with a robot. Levin's work in these two novels explores the depths that one will go for personal comfort, for perfection.

Both works bind the reader's hands and force them to watch as unique, self assured women are undermined by their partners and crushed beneath the dreary weight of simple desires. But it's The Stepford Wives that proves to be darker and prescient. There is no demon from the beyond controlling the machinations of the men of Stepford. Every sin committed against the women in this story is committed by a human hand.

How to get that Stepford look

There's a look to the Stepford Wife that was dreamed up in the '70s but survives in its own way today. Forbes' 1975 adaptation created the style of Stepford: perfectly coiffured hair and form fitting, outfits that are somehow sexy and conservative. Frills, white gloves, and big hats. Their makeup is shellacked and not one eyelash is out of place. In the '70s the Stepford Wives wore pastels, skirts, and ruffles, but there's a version of that you can still find today.

In a 2015 blog entry on the seemingly defunct website Stepford University, the anonymous author writes that modern Stepford women should be "swans." The author says that these big, beautiful birds are everything that a would-be Stepford wife should be, graceful and tranquil. As a counterpoint here's a video of a swan trying to attack someone in their car.

Fembots they're not

Seeing the Stepford terminology so far removed from its source material is jarring, but not surprising. The women in the film are gorgeous even if they've been turned into literal automatons. Who wouldn't give up their personal freedom, private thoughts, and any semblance of humanity to live a perfectly wholesome life?

The Price Of Having It All

There's a famous quote about Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (reportedly taken from a 1982 Frank And Ernest cartoon) about how society perceives the accomplishments of men and women: "Sure, [Astaire] was great, but don't forget that Ginger Rogers did everything he did, ...backwards and in high heels." Feminism challenged the the traditional view of gender roles -- that men were the smart ones, the ones who belonged in charge, doing things of great consequence, and women were subservient by nature, fit to do easy and less consequential tasks that were denigrated as "women's work." Furthermore, a higher emphasis was placed on women's appearance; they were expected to look put together at all times, and to "keep" their figure -- important to "keeping" a man.

There was the condescending idea that women should aspire to "have it all" -- a perfect home, perfect kids, perfect marriage and perfect appearance -- and that this would bring satisfaction. But having it all sounds a lot like doing it all, doesn't it? Keeping everyone else happy and everything tidy requires a near abdication of self.

A Robot's Work Is Never Done

The sinister husbands in the film don't really want wives -- they want unquestioning multi-taskers who look and behave perfectly and appear to be happy about it.

They want robots, so they make robots.

The fact is, managing a household is complex, potentially soul-draining, and may have required more skill than the jobs the bread-winning men were doing. Striving for the Barbie-doll ideal, forever dieting while their beer-swilling husbands packed on the pounds and lost their hair, required a discipline those husbands couldn't (or chose not to) understand.

Another way of viewing the Stepford Wife is as a critique of the unfairness of traditional gender expectations. In order to be the perfect wife, you'd almost have to be a robot. And those seemingly perfect wives we all meet from time to time? Maybe they really are robots.

The Cult Film That Struck A Nerve, Sort Of

The Stepford Wives was neither a critical or commercial success. Earning only $4 million at the box office in 1975, the film was derided by genre film averse critics and second wave feminists who felt that the film was attempting to co-opt their movement with a shiny, beautiful facade. What people missed at the time is that the film is a warning. The bad guys win. Katherine Ross is choked to death with a pair of nylons by her robotic doppelgänger. It's every bit as harrowing as the final moments of Night of the Living Dead and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

In the years following the film's release it became a cult classic along the lines of Beyond The Valley of the Dolls and The Phantom of the Paradise. Each film offers its own perverse pleasures at a price.

Maybe You've Been Brainwashed Too

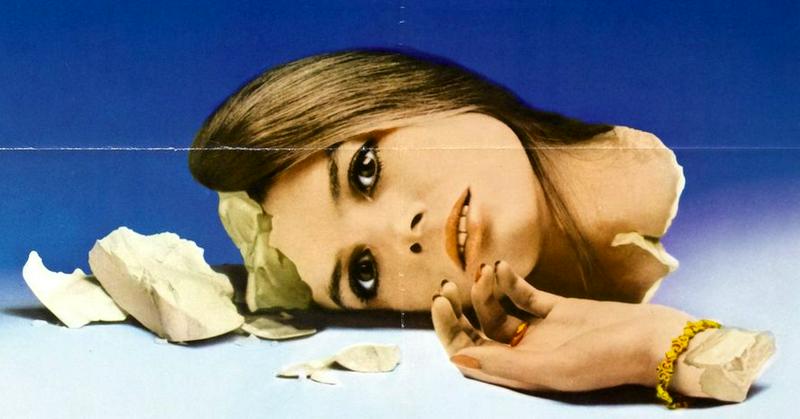

How did the title of a critical and commercial failure become the de facto term used to described docile, unthinking housewives? Viewers may not have sat through a two hour movie, but the imagery on the film's poster - Katharine Ross' head smashed like a porcelain doll accomplishes the same goal as the film but it does it in an instant.

Writing for Film Comment, Alissa Quart notes that many of the phrases we use to describe a group of people or a major event can be traced back to the social horror films of the '60s and '70s. Think Soylent Green, and The Manchurian Candidate, aren't we still calling people zombies thanks to George Romero?

The Worst Thing About Being A Robot Is Believing You're Not A Robot

Audiences may not have watched The Stepford Wives or Invasion of the Body Snatchers but those titles are the perfect shorthand for someone who's abandoned every shred of individuality for what they perceive to be a better life, even if that normalcy becomes a nightmare. Perhaps the spread of the phrase is best explained by Mary Stuart Masterson, who plays the young Kim in the 1975 film:

‘Stepford wife’ has become code for some robot following a script and meeting some male misogynistic ideal of femininity. [It’s about] negating your agency as a woman.