What is LSD? Albert Hofmann's Invention, Explained

By | November 15, 2020

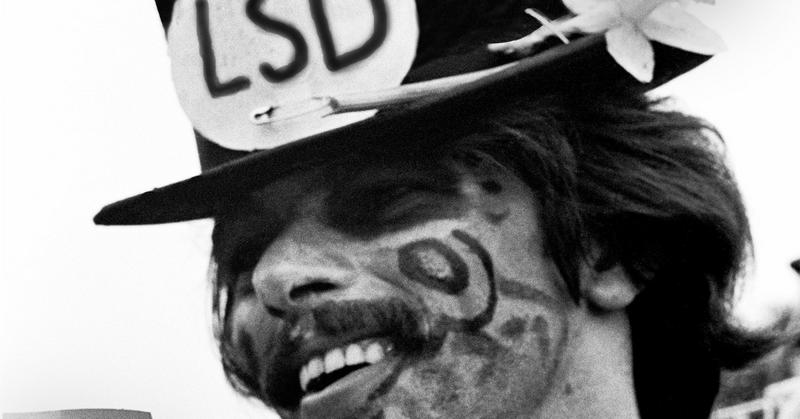

LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide, or acid) permeates '60s and '70s pop culture -- it was the catalyst for psychedelic music, art, literature and fashion. Even if you never tuned in, turned on, and dropped out, you know a little about this mind altering drug created by Albert Hofmann and popularized by artists like The Beatles, Timothy Leary, and Steve Jobs. There's more to this drug than just hippies in the park with flowers in their hair. It's been used in government testing, and through its disciples Lysergic acid diethylamide has changed society in ways that we can't comprehend. People who've never experienced psychedelics might know that LSD is dispersed in tabs printed on blotter paper, but they don't know the research and development behind this mind expanding, trippy substance.

From witchcraft to psychedelia

The main thing that everyone knows about LSD is that it gives the user intense hallucinations. This property comes from ergot, a fungus found in tainted rye that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people over centuries, while also causing the hallucinations and mania that led to accusations of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692 and 1693.

When consumed on its own, ergot can cause gangrene and convulsions. In the year 857 in a region of modern-day Germany, consumption of wheat poisoned with ergot caused a plague full of blisters and body parts that just sloughed off before someone died. The Swiss chemical company Sandoz wanted to see if there was anything they could do with something so poisonous and tests showed that small doses of the poison had positive side effects in childbirth by restricting blood flow.

Professor Arthur Still isolated the the compounds in ergot that caused the constrictions, ergotamine and ergobasine, and concluded if used in small enough dosages they could stimulate the respiratory and circulatory systems. He called the chemical manufactured from the active compound in ergot lysergic acid.

LSD was discovered accidentally

As with many of history's greatest discoveries, chemist Albert Hofmann stumbled upon LSD by accident. On November 16, 1938, Hoffman was researching medically useful ergot alkaloid derivatives in Basel, Switzerland, basically just combining lysergic acid with different organic molecules, when he synthesized LSD-25.

At the time Hofmann didn't realize the psychedelic effects of the 25th chemical combination, but after accidentally ingesting some of the chemical in 1943 he realized that he had his hands on a powerful substance. Later that year he ingested 250 micrograms of LSD and had an extremely heavy trip. Hofmann described his first trip to his boss in a memo written to explain why he had to leave work early:

I was forced to interrupt my work in the laboratory in the middle of the afternoon and proceed home, being affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dream-like state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted steam of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.

Albert Hofmann's second self-test led to a similar outcome, only this time he had a lab assistant take him home. The only problem was that the two men were riding bicycles. Undeterred by its psychedelic effects, Sandoz Laboratories put LSD on the market in 1947 as a cure all for mental issues, be it alcoholism or the all encompassing "criminal behavior."

The first trips were incredibly disorienting

Even if you've never experienced a trip you definitely know what it is. When Hofmann first started his home home research into LSD he attempted to codify the experience of taking the chemical, but that proved to be more or less impossible. Instead, he made a ton of journal entries that show the disorientation that he felt while dosing himself that he didn't really understand. Hofmann's early takeaway from his research is that LSD made him dizzy, thirsty for milk, and he had trouble placing people that he knew in his everyday life. He wrote:

Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. They were in continuous motion, animated, as if driven by an inner relentlessness. The lady next door, whom I scarcely recognized, brought me milk—in the course of the evening I drank more than two liters. She was no longer Mrs. R, but rather a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.

It wasn't the ideal trip, but as Hofmann came to understand the chemical he found that his negative experiences came from his own unfamiliarity with the chemical and not the chemical itself. Hofmann later realized that if he ingested LSD with a positive attitude things went smoother, and he continued taking the drug for the rest of his life.

LSD testing has always been morally iffy

Compared to many other drugs (pharmaceutical and illegal), LSD doesn't really have any negative side effects. Bad trips are possible, but it's not an addictive substance, and it's not deadly like a lot of the harder drugs on the market. But to discover its characteristics, researchers conducted a myriad of tests that wouldn't fly today.

LSD was tested on animals pretty much across the board: cats, mice, fish, chimps, they've all been dosed under the auspices of science and none of them suffered acute harm at the active dose, although it likely freaked them out. Hofmann continued testing himself outside of the lab, later saying that the psychedelic experiences from this era instilled within him "a feeling of ecstatic love and unity with all creatures in the universe."

In the 1950s, LSD testing came to America via the CIA. At the height of the cold war, the organization was searching for a mind control drug and they thought LSD was the ticket. CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb led the program, dubbed MKUltra, and after buying the world's entire supply of LSD for $240,000, distributed it to hospitals, clinics, and prisons where research projects were carried out to see how people reacted to the drug. Their hopes of the perfect mind control drug were dashed fairly early on, and actually led to the counterculture of the 1960s.

Can LSD help the human brain?

Aside from the CIA's morally unsound LSD tests, a large amount of the testing that's been done with LSD has yielded positive results. Researchers have found that low doses of LSD have helped to improve focus and performance, although the results are purely anecdotal as of this writing. In the '50s and '60s there were psychedelic therapy tests that looked to unblock subconscious material while producing self-acceptance. Most notably, LSD seems to be a tool for unlocking, or at the very least harnessing creativity. A researcher named Oscar Janiger felt that LSD was akin to a "creativity pill," and found that through guided psychedelic sessions it was possible to work users into a state where they're more creative.

With all of the research being done with LSD, there's still a lot to learn about this chemical. Even if you're never going to try the drug, it's important to know where it came from and the reasoning behind its creation. You may have visions of hippies rolling through fields out of their minds on acid, but just like Aspirin and every medicine you can find on the shelves, LSD was created in a lab by people who were trying to help humanity. Writing of his later experiences with mircrodosing LSD, Hofmann wrote:

I see the true importance of LSD in the possibility of providing material aid to meditation aimed at the mystical experience of a deeper, comprehensive reality. Such a use accords entirely with the essence and working character of LSD as a sacred drug.