Capitol Bombing Of 1971: What Was The Weather Underground And What Did They Want?

By | February 28, 2021

In the early 1970s, the Weather Underground carried out a series of bombings against targets including the U.S. Capitol and the Pentagon. The group's aim to form a "classless communist world" never came to fruition, but the often violent tactics of the Weather Underground took the beliefs of the anti-establishment movements of the '60s and '70s to their extremes.

In the 1960s, college campuses were buzzing with the move for social change. Meeting at sit-ins, rallies, and secret meetings, groups of revolutionaries and formed from disparate participants with the aim of bringing revolution to America. For the Weather Underground, that revolution was to be achieved by any means necessary.

Beginning as a faction of Students for a Democratic Society, the Weather Underground declared all out war on the United States of America. Their transgressions made in protest against the Vietnam War ranged from staged riots to a series of bombings perpetrated against federal buildings. On March 1, 1971, the group detonated an explosion at the U.S. Capitol to protest the invasion of Laos by the U.S. military, earning them the designation of domestic terrorists by the FBI.

A group within a group

The Students for a Democratic Society were trying to bring together people living hand to mouth with the Economic Research and Action Project between 1963 and 1968. While trying to mobilize people from lower economic classes to strive for a guaranteed annual income and more political rights some members of the group felt that they were getting nowhere with community organizing. They felt that they needed to do something radical -- they felt they had to create chaos.

A split occurred within the group between members who favored non-violent tactics and those who felt that a more direct means of action was needed for change to actually take place. They felt that peace protests, sit-ins, and hunger strikes would do nothing to take the American military out of Vietnam and that it would do little to change life at home. Following the the 1969 murder of Black Panther Party member Fred Hampton at the hands of the Chicago Police Department, the men who made up the Weathermen made an existential break with the United States and prepared for a more basic break with the SDS.

You don't need a weatherman to know the way the wind blows

In June of 1969, the SDS held the first of two conventions that year, and the group was already ripping apart at the seams. As the convention got underway, a manifesto titled "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows" (taken from a line in Bob Dylan's "Subterranean Homesick Blues") detailed the action to be taken by the group soon to be known as the Weathermen. The group explained the need to take clandestine revolutionary action to bring an end to the war in Vietnam.

During the June convention, the group planned to "bring the war home" as a means to "shove the war down [the U.S. government's] dumb, fascist throats." Members of the group traveled to Cuba one month later where they met with representatives from North Vietnam and discussed tactics and training. In 1975, a Senate Judiciary Committee alleged that the group also received explosives during this visit.

Days of rage

The Weathermen's first strike was a planned series of riots known as the "Days of Rage." Meant to serve in opposition to peaceful sit-ins, the group hoped to bring together thousands of like-minded individuals who were willing to be arrested, injured, or killed in the name of ending the Vietnam War. Former leader of the Weather Underground, Bill Ayers, notes that he was disappointed that only a few hundred people showed up in Chicago on October 8, 1969, rather than the thousands that were promised.

Even with a smaller number of demonstrators the group still made themselves known. On October 8th, around 300 people rioted through the Gold Coast neighborhood on Chicago's north side, smashing store windows and mixing it up with the police. The police were unprepared but quelled the protestors with tear gas while running at least two squad cars through the crowd. At the end of the first day, 68 rioters were arrested and a number of the Weathermen were injured but they continued on with their plan.

Two days later, 300 members of the group marched through The Loop under heavy police surveillance before breaking through police barricades. The protestors made a bee line for shop windows, smashing them before destroying cars on the street. In two days of rioting the Weathermen caused $35,000 in damages and accrued $243,000 in bail fees.

The Weathermen go underground

In the final days of 1969, the group held a series of meetings in Flint, Michigan to discuss changes within the organization. Rather than planning elaborate riots and protests, the group decided that they needed to carry out more focused guerilla tactics. The first act of the new version of the Weathermen was carried out on February 21, 1970, in New York City.

At the time, members of the Black Panther Party were in a pretrial over a plan to detonate explosives at the city's landmarks and various department stores. In solidarity with the Panthers, members of the NYC arm of the Weathermen tossed three Molotov cocktails into the home of the presiding judge, New York Supreme Court Justice John M. Murtagh.

More Molotov cocktails were thrown into Columbia University's International Law Library, at a parked police car in the west village, and at the Army and Navy recruiting booths on the Brooklyn College campus. Less than a month later, members of the Weather Underground living in Greenwich Village were killed in an explosion when one of the bombs they were storing exploded, setting of a chain reaction with the rest of the explosives in the home. Diana Oughton, Ted Gold, and Terry Robbins were killed in the blast. In a report on the explosion, the FBI claims that the group was housing enough explosives to destroy both sides of the street.

A shift in strategy

After the deaths of their friends in New York the remaining members of the Weather Underground met in California to rethink their strategy. They felt that it was important to destroy public and government property to remind Americans that the U.S. government was responsible for what was happening in Vietnam, but they didn't want to hurt anyone. They began picking targets that would be empty during the evenings, and they went out of their way to make sure that no one was in the area when an explosive was detonated.

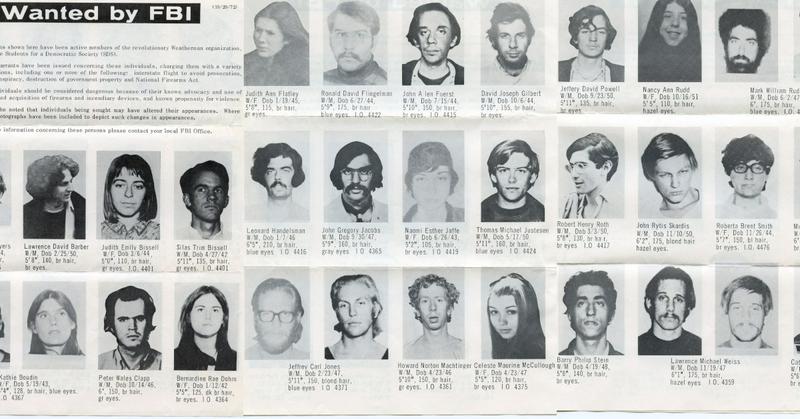

On June 9, 1970, the refined group of revolutionaries carried out their first attack: they blew up a New York City police station in response to the murder of George Jackson by prison guards in San Quentin. Six minutes before the explosion the group notified police of the explosives in place. This action earned the group a spot on the FBI's ten most-wanted list of 1970. In September of that year the group received a $20,000 donation as payment for breaking LSD activist Timothy Leary out of a federal prison before secreting him and his wife to Algeria. Leary later informed on the Weather Underground to the FBI in spite of writing in his 1983 memoir that he didn't "want to be called a snitch." None of Leary's information led to criminal charges for the group.

The bombing of the Capitol

On March 1, 1971, the group carried out their most destructive plan yet when they placed a bomb inside the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. The explosions blew out the windows of the building and racked up $300,000 worth of property damage, but there were no causalities. On May 19, 1972, the group placed an explosive device inside a bathroom at the Pentagon to celebrate Ho Chi Minh's birthday. Once again, no was hurt but the explosion did cause flooding and the destruction of government computer systems.

All of this destruction of property was racking up criminal charges for the group while they continued to break apart and come back together in various forms over the next few years. In 1971, a group calling themselves the "Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI" broke into an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania and made off with files on the entity's COINTELPRO operation. With COINTELPRO, J. Edgar Hoover engaged in acts of intimidation and disinformation to completely upend anything and anyone he saw as anti-establishment. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lennon, the Black Panthers, and the Weather Underground were just a few of the people and groups that the FBI sought to destroy.

The FBI broke federal law by using undercover agents to gather information on the Weathermen in the name of what they felt was the "greater good." With the FBI's domestic spying out in the open most of the charges against the Weathermen were either dropped or lessened, specifically because agents broke into their homes without a warrant.

The end of a revolution

By 1976, the Weather Underground was in flux. Word about the FBI's COINTELPRO operation was out and and being debated in federal courts, and some members of the group wanted to go above ground. Black and Latinx members of the group felt that the white members of the WUO and their sub-groups pushed them to the side and only brought them in when dealing with racial issues. The group had lost their way, and member Jeremy Varon says that the Weather Underground ceased to exist in 1977.

Most of the members who went above ground following the reckoning of the FBI's illegal acts received large fines and short stints of probation. In 1980, Bill Ayers turned himself in. All of his charges were dropped. Members who remained underground continued carrying out violent political theater. In 1981, Kathy Boudin, Judith Alice Clark, and David Gilbert, now members of the May 19 Communist Organization (one of the many WUO splinter groups) robbed an armored Brink's truck in Nanuet, New York. The robbery went sideways and three people were killed in a firefight. Boudin, Clark, and Gilbert were each sentenced to at least 20 years in prison.

The robbery of the Brinks truck was the final nail in the coffin for the Weather Underground, even as fractured as it was. Even though the group has been described as a domestic terror organization many of its former members have gone on to hold positions in higher education and they've continued to work as peaceful activists for a variety of causes.