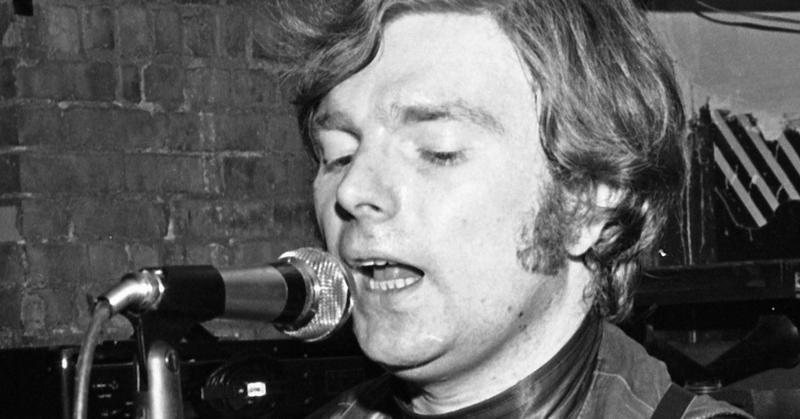

1968: Van Morrison Risks His Life & Career For 'Astral Weeks'

By | July 8, 2019

The story behind Astral Weeks, Van Morrison’s landmark album, is fraught with bad decisions, angry record executives, and the mafia. The short version of the story is that Morrison didn’t want to work with his then-current label, so to get out of his contract he recorded an album full of unreleasable nonsense songs. He also had to buy that contract back from mobsters for $20,000 in order to he make the jump to Warner Bros. Free from his former contractual obligations he recorded the album with a bunch of jazz musicians without telling them what to play. According to everyone who ever worked on the album, Morrison never introduced himself and just told them to play whatever they felt like playing.

Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks is an anomaly in 1968. It’s a jazzy pop record that slips in and out of time signatures with little regard for what was then cool or hip. It was the same year that saw The Beatles (or the "White Album") and the first album by The Doors. This seminal piece of music went underappreciated for decades and by all accounts, it almost didn’t exist.

Morrison got in his own way during the writing and recording of his album, but somehow the stars aligned and after three sessions of long takes Astral Weeks was born.

Morrison’s dispute with his label killed its owner

After finding early success in the United States with the single “Brown Eyed Girl” on Bang Records, Morrison wanted to change up his sound and do something different, but label owner Bert Berns didn’t see things that way, and because he owned Morrison’s contract he put the singer-songwriter on ice. Morrison continued making trouble for Berns, so much so that Berns suffered a heart attack in a New York hotel room on December 30, 1967.

Now, it’s not Morrison’s fault that the head of his label suffered a heart attack, but Berns’ wife Ilene felt that the singer was directly responsible and she went out of her way to make his life a living hell. Her vindictive sense of obligation to her former husband might be just one of the things that inspired Morrison to get out of New York City.

Morrison’s new label head tried to have him deported

As if it wasn't bad enough that Morrison couldn’t record new music, he was in the middle of having the paperwork renewed to keep him in the United States legally. The late Bert Berns had been working on the paperwork when he passed away, so the new label boss (and Bert’s former wife) contacted immigration services in order to put heat on the singer.

Morrison married his longtime girlfriend, Janet Planet, which more or less handled his immigration problems, but now his recording contract was in the hands of the mob. Whether the mob owned the contract prior to the death of Berns or if they got their hands on it afterward is unclear, but after a member of the mob smashed a guitar over Morrison’s head one night he decided to pack up and move to Boston.

The singer recorded three albums worth of nonsense songs to get out of his contract

Before he could start working on any new music, Morrison had to do a couple of things: He needed to buy himself out of his contract for $20,000, and he owed his old label a collection of songs that they could use to puff up their publishing house. Rather than give in and record Astral Weeks for Bang, Morrison went to a studio and cut 36 nonsense songs in one long session.

The songs are completely ridiculous and sloppy, and they’re more middle fingers to his old label than attempts at writing anything good. The songs, all of which are available on YouTube, have titles like “You Say France and I Whistle,” “The Big Royalty Check,” and “Want a Danish?” and they all shake out around a minute or a minute and a half. This half of his obligation fulfilled, he now had to pay off the mob.

Warner Bros. bought Morrison’s contract from the mob

Warner Bros. really believed in Morrison and they wanted him under contract, so they did what any good label would do and paid the mafia $20,000 in cash to buy him out of his contract. Record executive Joe Smith said that Morrison was “a hateful little guy” but he was in love with his voice, so he personally delivered a sack full of cash to a group of mobsters on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. He said:

I had to walk up three flights of stairs, and there were four guys. Two tall and thin, and two built like buildings. There was no small talk. I got the signed contract and got the hell out of there, because I was afraid somebody would whack me in the head and take back the contract and I’d be out the money.

Morrison didn’t speak to any of the musicians on the album

Free to record his album, Morrison hit the studio with producer Lewis Merenstein, but he faced one more hurdle: he wouldn’t be able to record with the musicians he’d been playing with for the last year. Instead, Merenstein recruited a group of jazzy studio hands who were used to recording commercial jingles. Morrison wasn’t enthused with the idea of playing with hired guns, but he wanted to get the record finished.

According to the guys on the session, Morrison didn’t speak to anyone when he arrived, and he didn’t provide any lead sheets for the musicians. Instead, he played the songs through a couple of times for the musicians before retreating to the vocal booth where he stayed for the remainder of the recording.

At the time Morrison hated “Astral Weeks”

After all was said and done Morrison couldn’t be bothered with his record. The musicians who played on the record loved it, but Morrison later said:

They ruined it. They added strings. I didn’t want the strings. And they sent it to me, it was all changed. That’s not Astral Weeks.

The album didn’t shoot to the top of the charts by any means, and it more or less disappeared from stores in 1968, but through word of mouth the album endured. People are still enamored with the album, and its influence is still being felt in the waves of pop culture.