The Jerk: How Steve Martin Found His Rhythm

By | June 28, 2022

Steve Martin got his start writing comedy, before transitioning to standup comedy, and then, with The Jerk (1979) into acting. In the film, Martin’s first, he plays Navin R. Johnson, the adopted son of black sharecroppers. Although he is unaware of his adoption, it is clear, not just because of his skin color, but also because he has no sense of rhythm. He hears a rendition of “Crazy Rhythm” on the radio and starts to dance. He interprets this as a sign that he should head to St. Louis, where the song was broadcast. He stops in a hotel, where a dog barking at his door wakes him. Assuming that the dog is alerting him to fire, he wakes other guests. He adopts the dog and calls it “Shithead” based on the suggestions of the other hotel guests.

He Goes From Rags...

Navin begins working at a gas station, where he also gets a room. This leads to his address being listed in the phone book, where a madman finds it and decides to target him as a “random victim bastard.” While Navin is helping a customer, Stan Fox, with his glasses, he stumbles on a new invention, and Stan offers to split the profits with Navin if he can market the invention. When Stan leaves, the madman, who sees his opportunity, shoots and misses. The madman then chases Navin to a traveling carnival, where Navin finds a job as a weight guesser and meets Marie, and falls in love with her. When she leaves him because he is not financially secure, he tells Shithead to find a better master but changes his mind.

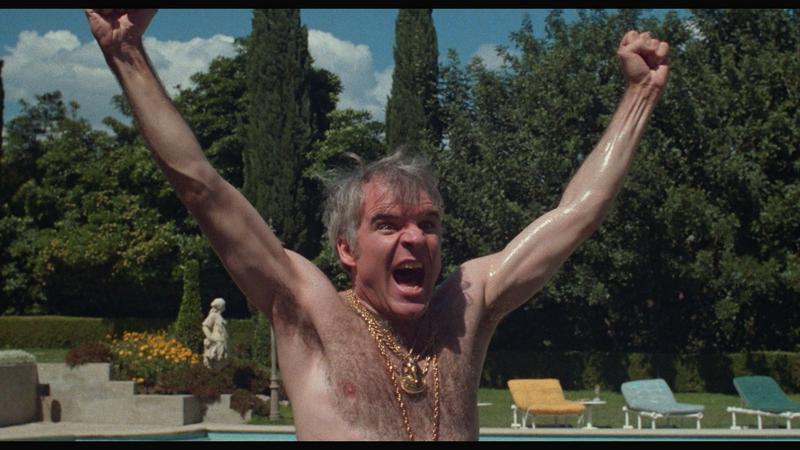

To Riches And Back To Rags

Stan Fox contacts Navin to tell him that he is selling Navin’s invention, which he has called the Opti-Grab, and Navin is entitled to half the profits. Their lives change, and they live extravagantly, until the “motion-picture director” Carl Reiner files a class-action lawsuit against them, claiming the Opti-Grab caused his eyes to be crossed, resulting in the death of a stunt driver in the film he was directing. After the complainants are awarded $10 million (which comes to $1.09 for each victim), Navin is bankrupt and depressed. He tells Marie to stop looking at him like he was “some kind of a jerk,” and he ends up homeless, resigned to a life of misery. However, everything turns out okay in the end, as Marie shows up with Shithead and his adoptive family, who had invested the little bits of money he sent them and were now comfortable. In the end, Navin manages to gain perfect rhythm and dance with his family.

Working With Carl Reiner

In 1977, after the success of his standup career, Martin wanted to cross over into film. He proposed a film based on a line from his act, “It wasn’t always easy for me; I was born a poor black child.” He gave his notes to David Picker who went to Universal Studios, taking the notes with him. At Universal, Martin was allowed to choose his director; he chose Carl Reiner, a choice that worked out well, as the two carpooled to work each day (this was in the midst of the gas shortage). At first, the film was supposed to be called Easy Money, but once Martin and Reiner started talking, a new title arose from their conversations. Martin knew that the title needed to be “short, yet have the feeling of an epic tale.” As he said, “Like Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, but not that. Like The Jerk.” Apparently, the choice of the director not only led indirectly to the title of the film but also to what Martin called “a joyful set” where the cast and crew ate lunch together daily.

Where The Humor Came From

He co-wrote the script with Carl Gottlieb and Michael Elias and adapted additional parts of his standup routine for the film; for example, he remarks “I don’t need anything” as he leaves a scene, picking up everything he passes along the way. However, not all of the funny moments came from the three of them, as one was inserted at the last minute by Reiner, a scene that took Bernadette Peters by surprise: the scene where Navin licks Marie’s face.

It Was A Low Budget Success

The low-budget film (it was made for a mere $4 million) was considered a box office smash, as it brought in $73 million domestically and $100 million worldwide. It was the eighth highest-grossing film of 1979. The critical response was mixed, with Janet Maslin of the New York Times saying that it “is by turns funny, vulgar, and backhandedly clever, never more so than when it aspires to absolute stupidity.” It has been ranked on a number of best comedy film lists.