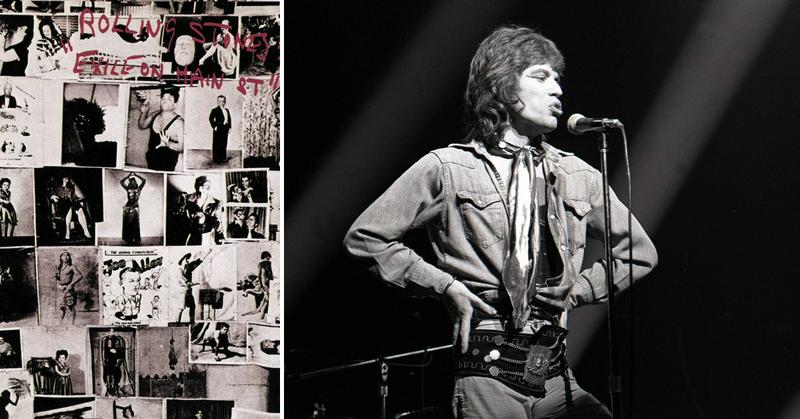

Exile On Main Street: The Rolling Stones' Best Album Is Released In 1972

By | May 10, 2020

A great Rolling Stones album born out of chaos -- such is the story of Exile On Main Street. On the run from the British government and evading a particularly nasty business agreement, the Stones went into exile in France. When they returned to public life they did so with the most beloved album of their career.

Recorded during a dark time filled with sex, drugs, and bad vibes, the album is the sound of Keith Richards searching for a fix and Mick Jagger trying to keep the band out of debt. During the band’s stay in France there were drugs, fist fights, speed boats, and debauchery. If something could go wrong, it did.

Somehow in this melee of psychosis the Rolling Stones recorded the album that the band was working towards for their entire life; a distillation of rhythm and blues, honky tonk, and rock ’n roll, Exile on Main Street isn’t a collection of songs, it’s a force of nature.

The Stones escape to France

By 1970 the Rolling Stones were on the run. The specter of death hung over the band from their disastrous concert in Altamont a year earlier that ended with the stabbing of Meredith Hunter and the mysterious drowning of Brian Jones. The group was broke, they owed the British government gobs of money, and word on the street was that their assets were on the verge of being seized.

Rather than wait around to see what happened the Stones lit out for the south of France where they could live like outlaws and avoid the taxman. Mick went to Paris, Keith moved into Nellcôte, a villa in Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice, and the rest of the band settled in the south of France.

In France the twin driving forces of Mick and Keith separated, each with their own hole to fill. Keith was propelled by dope - the jolt he got from banging it, the need for more - while Mick was running on fumes, trying to keep the band working until they had a record in the can. Once the record was mixed the band could hit the road and the road meant money. First they had to survive France.

Rocking in the basement, rolling upstairs

The basement of Nellcôte was where the magic happened. It’s where Jagger toiled with the help of Charlie Watts, Bill Wyman, Mick Taylor, a handful of studio musicians, and recording engineers while they all waited for Keith to wake up bless them with his presence. More often than not the band didn’t get cooking until midnight. Charlie Watts, the low key coolest member of the band spoke about the recording of the album, saying that it was dictated by Keith’s night owl, junk fueled habits:

A lot of Exile was done how Keith works, which is, play it 20 times, marinade, play it another 20 times. He knows what he likes, but he's very loose.

Keith spent his days trying to score dope, doing dope, sleeping off a hangover or playing his Gibson acoustic in his giant Louis XVI bed before wandering downstairs long after dark to see what he and the boys could conjure.

Dante’s Inferno

As the Stones spiraled into darkness throughout the ‘60s, separating themselves from the hippies and goofy, fun loving bands concerned with the dawning of the age of Aquarius it’s no surprise that they were obsessed with gloom surrounding Nellcôte. Occupied by the Nazis during World War II, the basement where the band recorded was adorned with swastikas carved into staircases and ventilator grates. Richards described descending into the makeshift, underground recording studio as entering Dante’s Inferno.

It wasn’t just the idea that the group was recording in a Führerbunker that made Exile an arduous experience, the humidity along the French Riviera detuned guitars, it made drum heads feel like pudding, if there was a worse place to record an album the Stones probably would have opted for it.

The layout of the basement hampered communication between the band and the recording engineer in the group’s mobile set up which meant that producer Jimmy Miller had to run back and forth from the basement to the truck, dodging drunks, dope fiends, and groupies to make sure that the band got a good take.

A never-ending party in exile

While the band was trying to find their way through the mire in the basement there was a whole other scene happening upstairs. Hangers-on, new friends, and drug buddies were coming out of the woodwork to buddy up to Keith and they all created their own kind of trouble.

Anita Pallenberg was driving everyone in the Rolling Stones crazy. Keith Richards started sleeping with her when she was dating Brian Jones and Mick Jagger started sleeping with her while she was sleeping with Keith Richards, and during the recording of Exile she was just hanging around Nellcôte and using up Keith’s heroin. Her presence didn’t help the chaotic atmosphere but it wasn’t Pallenberg who was stirring up jealousy between Mick and Keith.

About a month into the recording of Exile, Gram Parsons and his new wife showed up to the Villa much to the chagrin of Mick Jagger. Even though the underground country star had been around for the recording of Sticky Fingers and maybe even helped out with “Wild Horses” it was Jagger who wrote the album’s climactic “Dead Flowers.” He didn’t need one of Keith’s drug buddies hanging out and stealing his guitarist. At the time Jagger was under the belief that Parsons wanted Keith to produce his next album and to tour with him. If that happened there would be no Stones for at least two years and Jagger couldn’t have that. Parsons was asked to leave by a member of the band’s entourage and the party carried on without him. Richards said of Jagger’s distaste for Parsons:

Mick and Gram never clicked, mainly because the Stones are such a tribal thing. At the same time, Mick was listening to what Gram was doing. Mick’s got ears. Sometimes, when we were making Exile on Main Street, the three of us would be plonking away on Hank Williams songs while waiting for the rest of the band to arrive.

For the most part the all hours bacchanal was fueled by heroin that Richards bought from Castilian dealers with a line on pure, uncut horse. After a kilo of the stuff was delivered to the villa Richards cut it himself while Parsons watched on, waiting for permission to dive in.

The junkie rhythms of the Rolling Stones

Like Kerouac’s On The Road or the early work of Bukowski, Exile on Main Street is fueled by the excess of its creators. Each member of the group was in their own doom loop of drugs and alcohol - Charlie Watts drank brandy until he couldn’t function, Jagger took uppers to keep the night manager hours of Richards, and Keith had a system for staying on his feet.

Americans had quaaludes, Europeans had Mandrax, and every day around two or three in the afternoon Keith woke up and popped a Mandrax along with a slug of whiskey. He shot dope and stayed upstairs listening to music until the sun went down. He didn’t go into the basement until well after polite society was settling down into their beds.

The Mandrax was so necessary to Keith’s schedule (it helped keep the shakes to a minimum and maintained his buzz throughout the day) that he named a speedboat after the drug. After a particularly good session Richards took the Mandrax II out of a spin on the coast. After a meal in town or across the water in Italy he passed out in the villa after the sun came up and started all over again.

The songs were culled out of endless jams

The band was in France for a month before any real recording took place. It’s hard to know exactly when recording began for Exile. It never really officially started; some of the tracks were held over from Sticky Fingers, it’s unclear what was recorded in June of 1970, and by many accounts (of people who can remember) the sweltering summer nights of 1971 are when much of the album was formed from endless jams soaked in booze and sweat.

Every night Richards, Mick Taylor, Charlie Watts jammed with pianist Nicky Hopkins, saxophonist Bobby Keys, drummer Jimmy Miller and horn player Jim Price while engineer Andy Johns did his best to keep up. Jagger joined when he was available and more often than not Bill Wyman was MIA, receiving credit on only eight of the 18 tracks.

Hours and hours of jams were carved down into songs, with Jagger shouting out vowel sounds until he turned those sounds into words, those words into poetry. In the midst of their rock ’n roll circus Exile formed itself from noise and the ugly beauty of a group burning itself to the ground.

The Stones leave France behind

By the fall of 1971 the non-stop party started to take its toll on the citizens of Nellcôte. People with the most tenuous connections to the Stones were coming and going, using whatever was on hand and going on about their day. The villa’s unspoken open door policy brought in a group of thieves who popped into the mansion unannounced and quietly left with nine of Richards's guitars, Bobby Keys's saxophone and Bill Wyman's bass without a word from the group.

As if that weren’t enough of an invitation to get out of France, one day the police followed up on a claim that Anita Pallenberg had given heroin to a 14-year-old girl (this has never been substantiated) and paid a visit to the villa. The French police only performed a cursory look around the home, but promised a full investigation. That’s all it took for the band to leave France for good with Richards exiting via his speedboat, once again an outlaw on the run.

Mick Jagger finished the album in Los Angeles

Separating the truth from the myth of Exile on Main Street isn’t as simple as talking to the band. Depending not just on the song, but on a specific take, the band members, city, studio, and year change. The recordings from Nellcôte are only a part of the album but they’re the most important piece of the story. Following the flight from France Jagger decamped to Los Angeles were he finished the record in Sound Studio. Vocals, overdubs, and mixing all in sessions that stretched from December 1971 until March 1972. He called in Billy Preston, Doctor John, and pretty much every session musician in Los Angeles to help fill out the vocal tracks that he found to be murky, drowning in the swamp of Richards’ Memphis by way of England rhythm and blues.

Would Jagger have preferred to make Exile in a studio with banker’s hours? Probably. But while speaking with The New York Times in 2010 he says that the album is less a place and more a time period, that no matter where it was recorded, from 1969 to 1971 the Rolling Stones would have made Exile on Main Street:

It wouldn’t be the same record without Nellcôte, but then it wouldn’t be the same record without what we did in London… It’s a good story to say that what was created at Nellcôte was a result of the incredibly decadent atmosphere… It’s probably true that the atmosphere affected the feeling of the music, and the sound of the studio. But you’ve no idea how much or how little. And in the end, it’s just a sort of myth, really.

As with everything else that has to do with Exile, Keith Richards is diametrically opposed to Jagger. In the same article from the Times he specifically cites Nellcôte as one of the most important factors in the sound of the album. He says that everything else on the album is simply “fairy dust.”

Exile is the sound of the Stones at their best and their worst

Released on May 12, 1972, Exile was a worldwide smash. As the Rolling Stones toured for the first time in three years the record held onto its number one position even as critics wrote that it was disjointed and inconsistent. Jagger has never liked the album, saying that he doesn’t understand what fans see in a record without any hits.

Perhaps what fans respond to is the feeling of Exile. The sound of a group of artists imploding or setting themselves on fire, or whatever metaphor you watts use. The Stones' appetites for drugs and bitter infighting only grew throughout the ‘70s, offering brief moments of brilliance like Goat’s Head Soup and albums that offer only the most watered down taste of the band’s brilliance.

The band never matched the feeling of Exile on Main Street again, after nearly falling apart in France maybe they didn’t want to.